Historical Resources

The Sanctuary and its Development

The sanctuary of Dodona has, like many ancient Greek sanctuaries, undergone several periods of development and change. What marks Dodona out as different from other sanctuaries is that for many centuries the site remained underdeveloped, with the sanctuary predominantly open air and made up of few, if any, permanent buildings.

From the Mycenaean era (1600-1100 BCE) through to the early 5th century (500 BCE), there are some indications of local habitation on the acropolis above the sanctuary, as well as in the eastern foothills of Mount Tomaros. There are also huts belonging to the late Helladic and Geometric periods, which have been unearthed beneath the bouleuterion and stoa, as well as refuse pits and ovens for baking food and firing pottery. There may have been mud-brick or wooden buildings for Zeus’ priests, the Selloi (whom Homer mentions in the Iliad, 16.233-238 and for the dedications brought by pilgrims to the site. Importantly, there was no temple of Zeus, and the only distinctive feature of the sanctuary was likely a ring of tripods around the sacred oak tree.

In the late 5th to early 4th century BCE, a small temple, the Sacred House or Hiera Oikia, with a pronaos and cella was built beside the sacred oak. This temple was not a dwelling place for Zeus, but rather housed offerings. Palm-shaped reliefs from the roof of this construction have been discovered. By the mid 4th century BCE, the acropolis had been fortified with a wall, interspersed with towers, that surrounded a settlement.

Further developments in the sanctuary in the mid-late 4th century include the construction of an isodomic circuit wall (uniform masonry blocks with the joint of one layer sitting atop the middle of the block below) that enclosed the sacred oak tree to join up with the existing temple. Pilgrims would have entered the new enclosure from the south-east. This wall was subsequently replaced in the second half of the 4th century with a larger circuit wall that included ionic colonnades along the north, south, and west. Extant stones to the south of the sacred house suggest a possible house for Zeus’ acolytes, which was later dismantled.

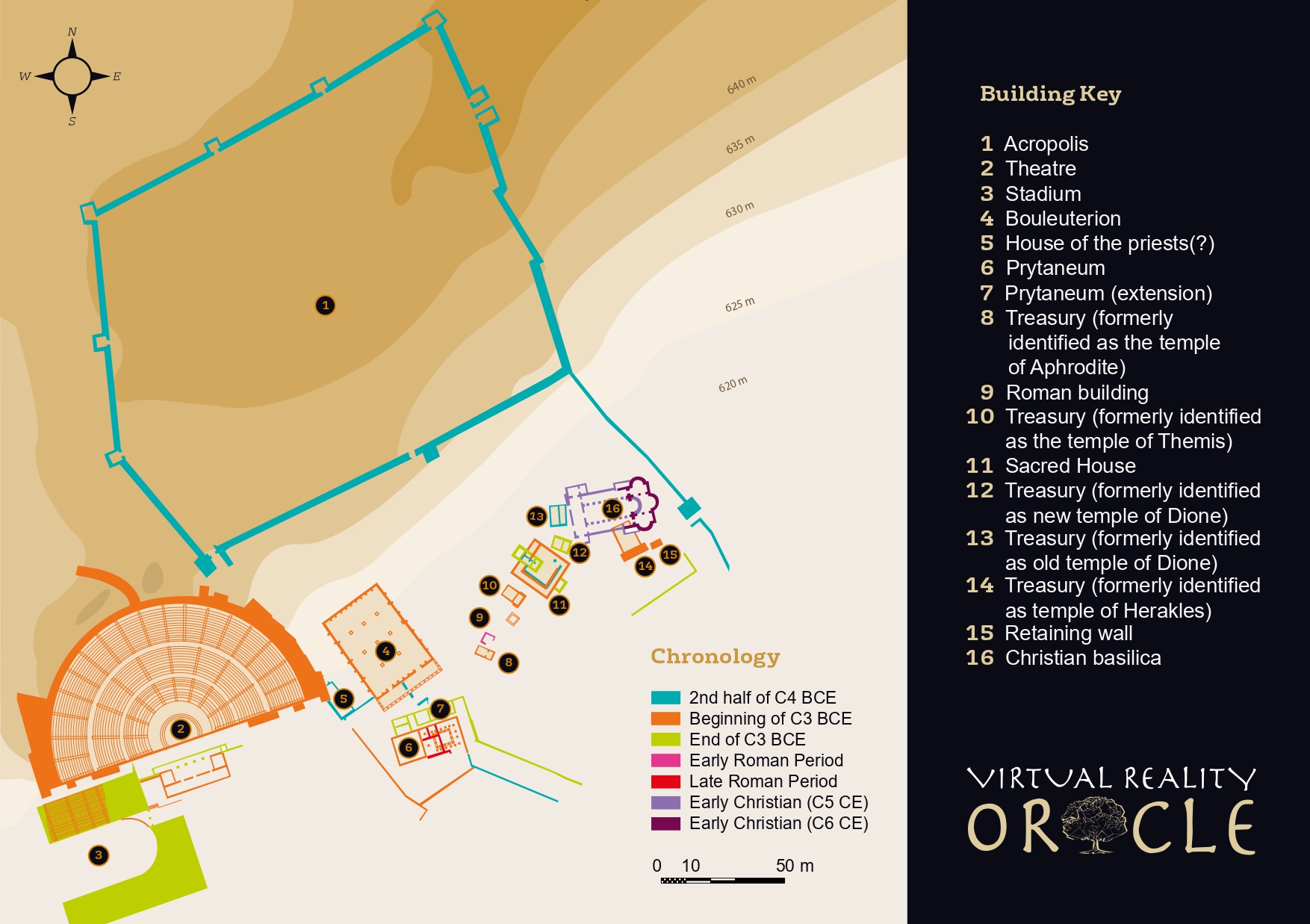

Other parts of the sanctuary continue to be developed in this period. By the beginning of the 3rd century, a finely worked circuit wall surrounded the sanctuary, running south towards the axis of the valley. A small building (Fig. 1, number 13) may have been a temple to Dione; further small buildings have been identified as temples (to Aphrodite, Themis, and Herakles), but more recent scholarship suggests that these were treasuries.

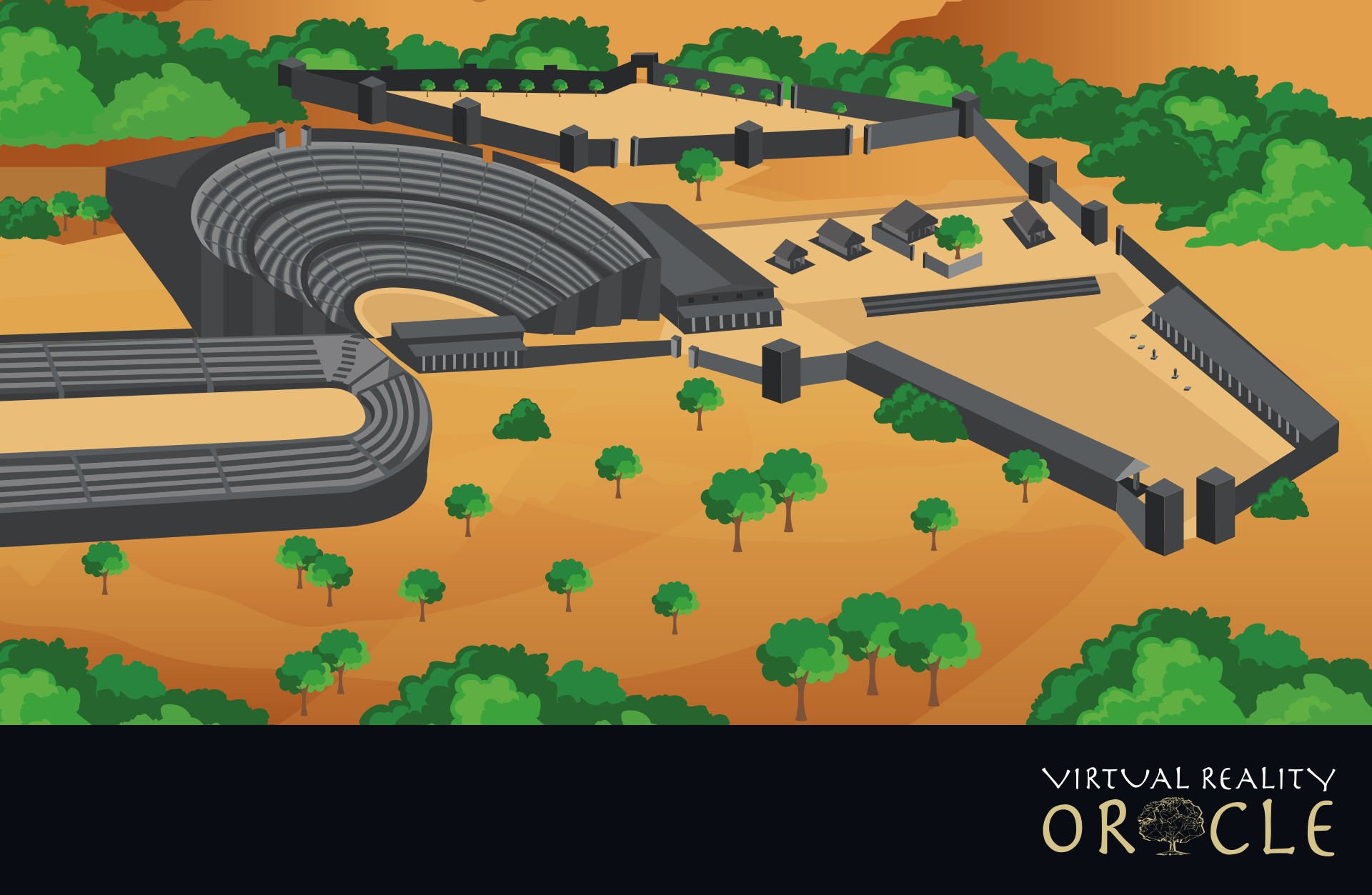

Under the reign of King Pyrrhus I of Epirus, Dodona became a more prominent political centre, and this was marked by the monumental architecture that comes to define the site. Pyrrhus enlarged the temple of Zeus, and built new temples for the other gods. He constructed a prytaneion (dining hall for magistrates), a bouleuterion (council chamber), and a stoa. He also built a 17000 seat theatre (one of the largest in Greece) along with a stadium, used to host the Naia festival, which was held in honour of Zeus Naios from the third century BCE to the third century CE.

At the end of the century, after the destruction of the site by the Aetolians, the sacred house was rebuilt. In the Roman era, a Christian basilica was built near to the sacred house using stones from the existing site.

References

- Chapinal-Heras, D. 2017. ‘Between the Oak and the Doves: Changes in the Sanctuary of Dodona over the Centuries’ in Simple Twists of Faith: Cambiare culto, cambiare fede: persone e luoghi - Changing Beliefs, Changing Faiths: People and Places, edited by S. Marchesini and J. Nelson, 17-38, Novoa. Verona, Italy: Alteritas.

- Chapinal-Heras, D. 2021. Experiencing Dodona: The Development of the Epirote Sanctuary from Archaic to Hellenistic Times. Berlin: De Gruyter.

- Dieterle, M. 2007. Dodona: Religionsgeschichtliche und Historische Untersuchungen zur Entstehung und Entwicklung des Zeus-Heiligtums. Hildesheim: Olms.

- Dieterle, M. 2012. ‘Dodona’. The Encyclopaedia of Ancient History, 26 October. Available at https://doi.org/10.1002/9781444338386.wbeah04090. (Accessed 1 November 2021).

- Emmerling, T.E. 2012. Studien zu Datierung, Gestalt und Funktion der “Kultbauten” im Zeus-Heiligtum von Dodona. Dissertation, Kovac. Julius-Maximilians-Universität, Würzburg.

- Mylonopoulos, J. 2006. ‘Das heiligtum des Zeus in Dodona. Zwischen orakel und venatio’, in Archaölogie Und Ritual. Auf der Suche nach der Rituellen Handlung in den Antiken Kulturen Ägyptens und Griechenlands, edited by J. Mylonopoulos and H. Roeder, 185–214. Wien: Phoibos.

- Piccinini, J. 2016. ‘Renaissance or Decline? The Shrine of Dodona in the Hellenistic Period’, in Hellenistic Sanctuaries: Between Greece and Rome, edited by M. Melfi and O. Bobou, 152-169. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Quantin, F. 2008. ‘Les oikoi, Zeus Naios et les Naia’. Kernos, Vol. 21, 9-48.